It’s no secret – modern agricultural systems could use a facelift.

Although vast fields of corn and soybeans are a marvel to behold, alternatives to monocultures are increasingly popular among large-scale growers and smallholders alike.

In the face of global challenges like natural resource scarcity, ecosystem decline, agricultural pollution, and rising input costs, many growers are opting to integrate sustainable farming techniques such as polyculture into their production systems, at once boosting their farm’s resilience and profitability.

Table of Contents

What Is Polyculture Farming?

Polyculture is not a one-size-fits-all solution. Defined as the simultaneous production of multiple plant species on the same piece of land, polyculture farming is a common practice throughout the world but can vary greatly in both size and scope, ranging from small polyculture gardens to large-scale agroforestry operations.

The motivations behind polyculture plantings include enhancing the sustainability of one’s operation, diversifying farm revenue streams, and even increasing ecosystem services such as pollination, biological pest control, and nutrient cycling.

Despite its benefits, many large-scale growers tend to avoid polyculture farming, instead of planting monocultures (or large swaths of a single crop) to allow for ease of cultivation and harvesting.

That being said, some innovative growers have leveraged new technologies and strategies to integrate polyculture at scale — to great benefit for both their farms and surrounding ecosystems.

Several examples of polyculture systems are described below.

Types of Polyculture Systems

1. Cover cropping

Cover cropping is among the most popular types of polycultures on modern farms. Cover cropping is the planting of non-commercial crops – often in diverse mixtures of carefully curated plant species – into otherwise fallow fields, with the purpose of increasing soil quality and reducing a farm’s environmental impact.

Although farmers can technically cover crop with a single crop, farmers typically employ diverse species mixtures to maximize the range of benefits observed. Plant species are selected based on myriad growth factors:

- Growing season

- Rooting depth

- Soil nutrient scavenging or nitrogen fixation abilities

- Drought tolerance

- Root exudates

- Biomass

- Growth habit

- Ecosystem services provided

- And compatibility with the subsequent main crop

Farmers often plant diverse cover crop mixtures of 10+ plant species to maximize the range of benefits, which include replenishing nutrients, soil fertility, and organic matter; improving soil structure; attracting pollinators and pest predators; reducing soil erosion and runoff, and weed and disease suppression. Some farms graze animals on cover crop, which allows for enhanced nutrient cycling and the diversification of farm products.

Of course, there are many ways to cover crop. While some farmers plant cover crops across entire fields and terminate the crop prior to planting their main crop, others opt to plant cover crop in alleys between their main crop rows, maintaining between-row plantings as perennial polycultures that can be grazed or mowed.

Farmers often plant diverse cover crop mixtures of 10+ plant species to maximize the range of benefits.

2. Companion planting

Growers operating at a small scale find many benefits from companion planting, or strategically planting certain plant species side-by-side. The agronomy of a given crop— including its root system type, rooting depth, and root exudates; vegetative growth habits; nutrient requirements, and more — all inform the compatibility of two plant species. However, just as certain crops can be friendly companions, some plant species can be incompatible foes, meaning their growth is hindered by one another.

There are many reasons for positive and negative synergies between plant species. For example, some crops may elicit certain chemicals from their roots that are toxic to other plants (i.e. allelopathy), while other plants may support different species by repelling pests or attracting predators. Some plants even alter the flavor of other plants!

Several examples of companion planting include the following:

- Heavy nitrogen feeders like corn and tomatoes are not a great pairing but do well with light feeders like basil and any nitrogen-fixing legume.

- Crops that require ample room for root development (e.g. potatoes) perform better beside shallow-rooted crops (e.g. lettuce).

- The vining growth habit of squash and climbing growth habit of pole-beans make them great partners to corn in a famous Mesoamerican system known as the “three sisters” or the “Milpa” polyculture system. While vining squash acts as a ground cover to shade the soil and retain soil moisture, corn acts as a support for climbing beans, with beans serving as a nitrogen-fixer for both corn and squash.

3. Intercropping

Intercropping, or the growing of multiple crop species in proximity within one field, is better suited to growers operating at scale than companion planting. There are multiple variations of intercropping, such as:

- Strip cropping, or planting different crops in adjacent strips, with strips sized large enough to allow for cultivation and harvest yet near enough to maintain positive synergies between plants.

- Relay cropping, or planting different crops into existing plantings, is another popular method. A corn-soybeans-winter wheat relay cropping system has proven to generate $100 more per acre compared to its mono-cropped counterpart.

4. Permaculture, perennial polycultures, and agroforestry

Permaculture is a catch-all term that includes various land-management strategies, such as perennial polycultures, agroforestry, and agroecology, which all aim to mimic natural ecosystem processes in growing food. Integrating perennial plants in a polyculture system maximizes certain ecosystem services, at once reducing soil erosion and runoff while increasing carbon sequestration and wildlife habitat.

Within these systems, a diverse mixture of plant species — from tall trees to small trees, from shrubs to herbs to ground cover — are selected and strategically combined according to their growth habit and growth rate; canopy structure; light, nutrient, and water requirements; nitrogen fixation capacity; rooting depth; root exudates; and more. Ultimately, the goal for a perennial polyculture might be to maximize plant-plant symbioses and crop yields while reducing management needs.

Examples of permaculture systems include vineyards interplanted with cover crop, with livestock grazing on between-row cover crop; shade-grown coffee interplanted with banana trees in the overstory and vegetables and medicinal herbs in the understory; and silvopasture systems that combine tree crops with grazing animals, such as chestnuts and mulberries with hogs.

Although many of these systems may seem “novel,” indigenous cultures throughout the world cultivated agro-ecosystems for millennia, integrating perennial and annual polycultures to grow food to positively shape natural landscapes.

Examples of permaculture systems include shade-grown coffee interplanted with banana trees.

Polyculture vs. Monoculture

Too often, agricultural commentators paint broad-brush generalizations about polyculture and monoculture farming systems, pitting one against the other as if the two are mutually exclusive. The truth is that polycultures and monoculture can co-exist on a single farm through crop rotations, seamlessly integrated across multiple growing seasons.

The respective benefits of polycultures and monocultures are as follows:

What are the benefits of polycultures?

- Better nutrient and soil use efficiency means healthier soils and reduced fertilizer inputs. Different plant species have different nutrient needs, root system structures, and rooting depths, meaning greater plant diversity on the farm can increase the range of nutrients scavenged by your crops. At the end of a crop’s lifecycle, these nutrients are returned to the soil as residue or leaf litter, contributing to greater soil fertility for diverse polycultures. Integrating diverse cover crop mixtures and nitrogen-fixing legumes can further reduce fertilizer needs. Additionally, polycultures often utilize the soil year-round, providing consistent ground cover that can reduce soil erosion, reduce fertilizer and pesticide runoff, and improve ecosystem impacts.

- Greater crop diversity means increased farm resilience and more stable yields. Diversifying your farm revenue by growing multiple crop species means your farm is less vulnerable to reduced crop yields caused by adverse environmental conditions. In fact, polycultures are often more resilient vis-a-vis natural disasters. For example, integrating perennial trees and shrubs as windbreaks provide protection from wind damage, not to mention shade for livestock during high heat events while integrating groundcover leads to greater soil moisture retention, mitigating the effects of drought.

- A healthier ecosystem reduces the need for pesticides, fungicides, and herbicides Polycultures that prioritize plant diversity lead to greater biodiversity in the local ecosystem, providing ample habitat for pollinators, as well as common pest predators such as hoverflies, praying mantises, spiders, and parasitic wasps. Even planting a small number of pollinator plants like sweet alyssum leads to large reductions in pest populations— and thus large reductions in the need for pesticides — thanks to biological best control. Additionally, strategic crop rotations that leverage the root exudates of different plant species can suppress plant pathogens and weed growth in the soil. For example, an oat cover crop has the ability to suppress disease in the soil, while rye is a well-known inhibitor of weed seed germination, which can lead to a reduced need for fungicides and herbicides. Although polycultures are not obligatory in organic systems, many organic farmers choose to integrate polycultures due to the pest management benefits.

What are the benefits of monoculture?

When planned and executed effectively, the benefits of monoculture include:

- Simplicity: Growing one crop allows for the simplification of farm management considerations and increased operational efficiency.

- Ease of Mechanization: Modern machinery is optimized for monocultures. The ease of mechanization allows for reduced labor costs.

- Land sparing: Greater efficiency can lead to higher yields, which in turn can reduce the amount of land needed to grow crops. This can lead to an overall reduction in the amount of wildlife habitat converted to agricultural use.

Integrating Polyculture and Monoculture Through Technology

Farmers throughout the world integrate polyculture and monoculture systems in creative ways.

While some farmers plant monocultures during the growing season and diverse cover crop polycultures during the off-season, others plant conservation areas (i.e. buffer zones) around their main crop, deploying diverse plant species to provide wildlife habitat and reduce runoff. Other farmers may selectively plant polycultures or monocultures based on the soil quality and topography of their land, with polycultures better suited to diverse, sloped, erosion-prone landscapes and monocultures better suited to flat, uniform fields.

As specialized farm technology and machinery are adapted to the needs of polyculture systems, it is likely that polycultures will become increasingly common in the developed world. Researchers have demonstrated how new technologies like variable-rate seeding systems can be used to plant polycultures at scale, while technologies like no-till drills allow farmers to plant their main crop directly into a polyculture cover crop. Novel simulation experiments and advanced algorithms, similarly, are illuminating best practices for polyculture systems in terms of companion planting, irrigation, and pruning strategies.

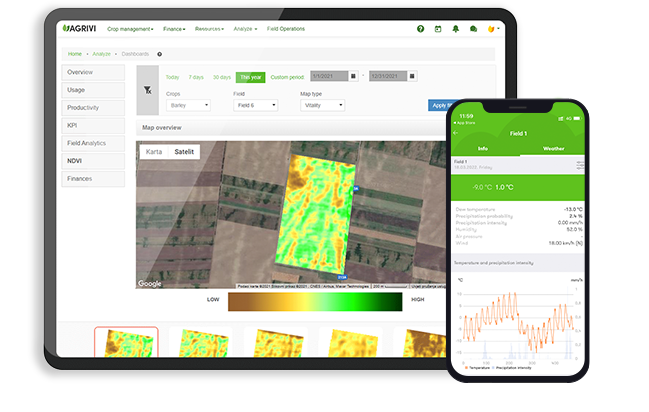

Managing Monoculture and Polycultures With AGRIVI

Whether growing a polyculture, monoculture, or something in between, every farmer needs a reliable system to collect and analyze data related to resource use efficiency, crop productivity, crop health, and profitability. Farm Management Software solutions like AGRIVI offer a user-friendly data management solution that generates real-time, actionable insights into your farm business.

And best of all? The software is crop agnostic, featuring over 160 plant species in its crop database. This means polyculture farmers can assign multiple crops to just one field in the digital platform, manage, record and track all farm data in one place.

Learn more: